Lucien Freud

47 paintings, 20 drawings, 14 etchings organised by the British Council

October 04 1991 / November 17 1991

Roma – Palazzo Ruspoli (60.000 visitors)

Catalogue – Electa

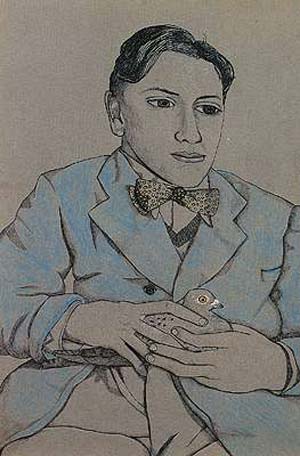

- Lucien Freud Ragazzo con piccione

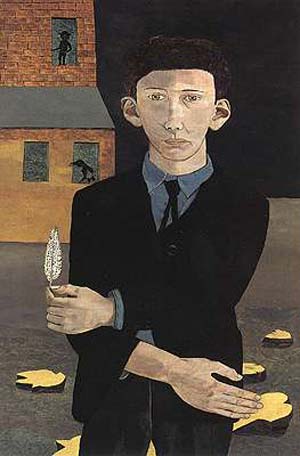

- Lucien Freud Uomo con piuma Autoritratto

- Lucien Freud Ragazza con gattino 1947

- Lucien Freud Ragazza con foglia di fico 1947

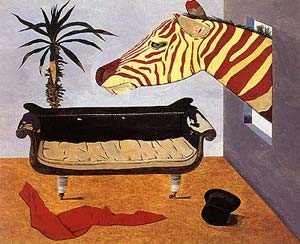

- Lucien Freud La stanza del pittore 1944

- Lucien Freud_Ammalata a Parigi, 1948

On October 3, 1991 Fondazione Memmo opens the first Italian retrospective exhibition dedicated to Lucian Freud. Created in collaboration with the British Council and curated by Bruno Mantura, the exhibition displays a rich collection of 47 paintings, 20 drawings, and 14 engravings, documenting the artist’s journey from the 1940s to the present.

Lucian Freud was born in Berlin in 1922 from Ernst, the youngest son of Sigmund Freud. The family, fleeing from Nazi Germany in 1933, settled in England, where Lucian became a naturalized British citizen in 1939. His talent as a draftsman and painter manifested early on, and in 1937, he enrolled at the East Anglian School of Art under the direction of Cedric Morris.

After the war, Freud visited France several times, including trips to Paris, and travelled to Greece and Italy. His early works showcased in the exhibition, such as “The painter’s room” (1943), “Man with feather (self-portrait)” (1943), and “Girl with a Kitten” (1947), exemplify his high-quality paintings. Despite being somewhat restrained in terms of expressionism, the young Freud’s cultural influences align with Neue Sachlichkeit (he looks at Grosz), with a focus on refined graphic solutions and a sensitivity to the meticulous drawing of Ingres, while also showing an awareness of surrealist influences.

Freud’s early production is a delicate balance between nature and history, where his strong sense of reality meets an interest in the Museum as a container – a rich source for verifying his work, adhering closely to figurative observation.

By the late 1950s, Freud decided to abandon drawing for a painting freed from any linear constraints. Brushstrokes took centre stage in his images, displaying more monumental renditions that seem to exhibit internal tremors and upheavals. Works from this period include “Man’s head” (1959/60) and “Sleeping head” (1962).

As the years progressed, Freud’s interest expanded beyond portraiture to the entire human figure, often depicted in absolute nudity. The artist, who never used professional models, captured the sometimes-tormented poses of his subjects through a kind of interaction between them and the painter.

From the artist’s penetrating gaze, reaching into the depths, those posing seem to want to defend themselves. Testaments to this are some splendid nudes like “Night portrait” (1977/78) and “Naked portrait II” (1980/81).

Freud’s artistic journey can be seen as divided between nature and history: on one side, his instinctive and conceptual adherence to realism, and on the other, a constant and vivid interest in the Museum that he frequently revisits. His latest daring and Michelangelo-inspired nudes provide evidence of this. It’s interesting to note that in the 1960s, a lively curiosity emerged not only in the cultural world but also beyond for the remarkable and indecent drawings of Pontormo. In his engagement between Museum and reality, keenly lived and observed, Freud reaches a stature that makes him one of the greatest artists of our century.